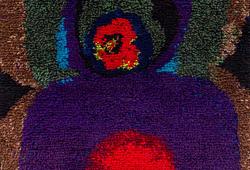

August Strindberg

"Packis i stranden" (Ice boulders on the shore)

On verso signed August Strindberg and dated 1892.

Oil on zinc 25 x 34 cm.

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Gustaf Brand, Lund, Sweden; Consul K. A. Warenberg, Malmö, Sweden; Mrs. Elsa Norlindh, Danderyd, Sweden;

subsequently as a gift; Bukowski Auktioner, Stockholm, Sale 556, "Klassiska Vårauktionen", 1 June 2010, lot 125; Åmells konsthandel, Stockholm; private collection.

Näyttelyt

Birger Jarls Bazar, Stockholm, July - September 1892, no. 2; Café A Porta, Lund, Sweden 1892; Nationalmuseum (National Gallery of Art), Stockholm, "Strindberg som målare och modell", 21 January - February 1949, no. 26; Örebro Centralbibliotek (Örebro Central Library), Rådhuset Örebro (Örebro City Hall), Sweden, "Strindberg som målare och modell", 24 February - March 1949; Lunds Universitets Konstmuseum (University of Lund Art Museum), Sweden, "Strindberg som målare och modell", 20 March - April 1949; Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf, "Der andere Strindberg", 25 January - 8 March 1981 (under the title "Packeis am strand"); Lehnbachhaus, Munich, "Der andere Strindberg", 18 March - 26 April 1981 (under the title "Packeis am strand"); Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Berlin, "Der andere Strindberg", 3 - 24 May 1981 (under the title "Packeis am strand"); Kulturhuset, Stockholm, "Strindberg", 15 May - 4 October 1981.

Kirjallisuus

Göran Söderström, "Strindbergs måleri", 1972, mentioned pp. 102, 236, 258 and 261. Reproduced full page, plate 13; catalogued under year 1892, p. 337 as no. 29.

"Packis i stranden (Ice boulders on the shore)" will also be included in the updated, revised and expanded edition of ”Strindbergs måleri” by Göran Söderström, with planned publication set for autumn 2017.

Muut tiedot

On verso landscape study as well as inscribed: "N:o 9" / "Property of K A Warenberg Malmö".

In the Swedish National Gallery exhibition catalogue "Strindberg –Målaren och fotografen" (9 February – 13 May 2001) [see also english version of the catalogue; "Strindberg –Painter and photographer", Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2001] Per Hedström gives the following picture of Strindbergs painting during the 1890’s:

"For Strindberg the 1890s were characterized by the so-called Inferno Crisis, which came to a head in Paris in 1896. For almost seven years he was unproductive as a creative writer. Instead he devoted himself to scientific experiments, and from time to time would paint. Now his painting suddenly becomes rather more than an amateur’s careful attempts to copy nature. The first reviews of Strindberg’s paintings appeared in the summer of 1892. He had just exhibited a small number of new works at a venue in Stockholm known as Birger Jarls Bazar, and the event attracted the attention of several newspapers. Some of the reactions were cautiously positive, but one could also come across the kind of ironically teasing review that has often plagued modern art".

The present work belongs to the group of a few works which were exhibited on this specific occasion. A reviewer writing in "Från Birger Jarls stad" ("From the City of Birger Jarl") suspected that Strindberg’s exhibition was a practical joke on the general public:

"In most cases it was very difficult to work out what the paintings were supposed to represent:

Whether ‘Snötjocka på hafvet’ (‘Blizzard’) is supposed to depict a dirty sheet hanging out to dry, or is an attempt to find a new way of painting barn doors, is impossible to say, just as one wonders whether ‘Packis’ (‘Ice Boulders’) is supposed to be a plate of bread and margarine or a dish of grilled veal trotters in brain sauce".

The critic also said:

"Regarding the 7 or 8 ’paintings’ that August Strindberg has amused himself by exhibiting at Birger Jarls bazar and that The Daily News has hastily written about as being poetic and with technical talent executed seascapes. I’m inclined to think that the rascal Strindberg, when he placed these little ’studies’ in broad gilt picture frames and sent them to the exhibition as ’paintings’ only wanted to play a little joke on the public and test the limits of the public understanding of art".

Such remarks ought to have both angered and hurt Strindberg who before the opening of the exhibition wrote the following in a letter from Dalarö to Sven August Peterson (lithographer and father of artist Hugo Birger):

"If any buyer for some unfortunate reason should happen to turn up, they are kindly asked to let the pictures in question remain in the exhibition! For the time being! You see, if the best pieces are removed and the critics are left to review the dregs, it would be unfair. Perhaps Kjerrman at D.N. [Daily News] would be able to have a look! Telephone him svp. With hopes for a great succés. Your ’old’ friend August Strindberg".

In "Strindbergs måleri" ("The Paintings by Strindberg") from 1972 Torsten Måtte Schmidt writes:

"Painting became to Strindberg something of a therapeutical pastime during the heartbreaking

divorce, but also Strindberg has made it clear that it was financial strain that forced him in to painting

in order to ’at all costs make money’ and that the exhibition was a deliberate move in that direction.

In a letter to Ola Hansson 13 September he also writes that he has been painting ’in order to sustain

life’ ".

As early as in May 1892 Strindberg wrote to Richard Bergh [fellow artist and later director of the

National Gallery of Art in Stockholm] to invite him out to Dalarö over Whitsun:

"I have a few studies, done after my imagination, that I would like to show you. A new ’-ism’ which I,

myself, have invented and would like to refer to as ’skogssnufvismen’ ’wood-nymphism’".

Per Hedström, once again, writes in the exhibition catalogue from the National Gallery of Art in Stockholm:

"The paintings displayed at the exhibition had been created while Strindberg was staying at Dalarö,

south of Stockholm, in the spring and summer of 1892. Strindberg had been having trouble getting

his plays produced, and his divorce from Siri von Essen was about to be finalized. For the first time in

nearly twenty years, he started painting in oils again. […] The 1892 paintings from Dalarö can be best

characterized as images derived from Strindberg’s memories of the outer archipelago and the open

sea. He was now refining and developing the range of motifs he had created during the 1870s; the

pictures are dominated by the open sea, the level horizon and extensive skies".

The leading expert on Strindberg as a painter and artist, Göran Söderström deepens the picture or

background in "Strindbergs måleri", 1972:

"After 25 June Strindberg was isolated at Dalarö udde, absorbed in an ever deepening sense or state of

hopelessnes. Possibly it is now that he creates a series of paintings executed on whatever material

happened to be at hand, particularly rectangular zinc plates, originally parts of a galvanic

element that Strindberg used for his scientific experiments. It was, however, another member of the

artist’s colony at Dalarö who succeeded in dragging Strindberg out of his state of despair and rub of

some of his own self-esteem and optimism: Per Hasselberg, the independent and self-asserted

sculptor, that Strindberg had met and taken a liking to in Paris. Hasselberg seems to have identified

and appreciated the novelty and originality in Strindbergs painting and encouraged him to go on.

Strindberg writes about Hasselberg in a letter to Carl Larsson 1894: ’He was my last and best friend in

Sweden and the only one who kept my spirits up, when the others trampled on or spat at me’.

Probably Hasselberg also helped Strindberg to acquire artist’s material from Stockholm. Only two

paintings on canvas remain from 1892; the reason why Strindberg prefered paper-panel or zinc is

with all certainty that the hard surface was more appropriate for his more and more advanced

technique with a palette knife".

The art public of today probably holds Strindberg’s paintings a lot higher than did his own

contemporary critics. The last word, however, is given to the artist himself who in a letter to Per

Hasselberg from Dalarö in September 1892 wrote:

"I shall not deny this blossoming of my youth’s first love: science which seemed to me like an autumnal

flower which had to bloom before the winter as well as the older flame; painting had to be reignited

before I died. […] Why is there not so much sense in this world that humans will allow artists

to work according to their own senses and not theirs".