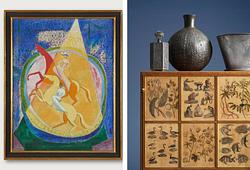

Ämbetsmannainsignia, Buzi, ett par, broderat siden. Qingdynastin, 1800-tal.

Tillverkad för civil ämbetsman femte rank, fågeln, en symbol över litterär elegans, är arbetad i silvertråd på en separat applique del som är fäst på en fyrkantig grund, som är broderad med en fågel som landar på en klippformation som träder upp ur skummande vågor där juveler och dyrbara ting skymtar fram. Runt fågeln ruyiformade moln, fladdermöss allt mot en mörk grund omgivet av en kantbård i guld, vitt och grönt. Fodrade med blått siden. Mått 30x27 cm.

Slitage.

Proveniens

Property of a private Finnish Collection.

The collection was formed between 1980-2020, the collector has had an interest in China and Chinese Works of Art since childhood, growing up in Beijing. He returned to China in grownup years for work, he came to live in China altogether more than 40 years. His love of China, and Chinese works of art is mirrored in the collection and being an academic collector, he never got tired of learning more about the subject by studying literature, attending lectures, visiting museums, auction houses and befriending curators from Beijing, Hong Kong, London, Paris, and Stockholm. The collection consists of both Chinese ceramics and textiles, This being part 2, a part of the textile collection.

Litteratur

Illustrated Precedents for the Ritual Paraphernalia of the Imperial Court, published in 1759, tells us much about how Court attire was regulated by imperial decrees. The Chinese tradition of wearing rank badges (buzi), also known as Mandarin squares, to demonstrate civil, military or imperial rank began in 1391 during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and continued throughout the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

These insignia were sewn onto or woven into the wearer’s garments to indicate their rank. Civil officials wore insignia with different bird species corresponding to their rank, while animals denoted military officers.

The fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 brought an end to rank insignia.

Övrig information

Qing badges feature a single creature and sun as well as ornamental borders with clouds and auspicious symbols. Appliqué animals began to appear on badges in the mid-19th century, which made it easier for officials to swap creatures as they moved up the ranks.

Although Ming portraits show women wearing identical rank badges to their husbands, edicts outlining rules for women were not issued until the Qing dynasty, when the wives and children of officials (sons and unmarried daughters) were permitted to wear their husband’s or father’s insignia. It became the tradition that a wife’s badge was a mirror image of her husband’s, so when she sat beside him (women sat on their husband’s left) their creatures would be facing each other. For example, a civil official’s wife’s rank bird would face left.