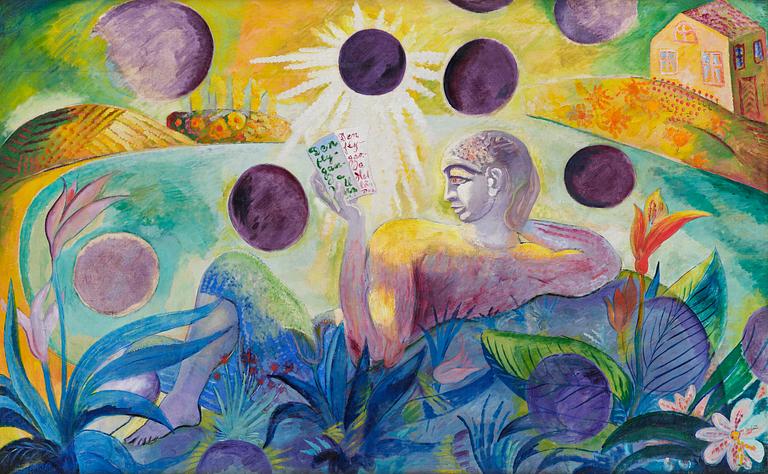

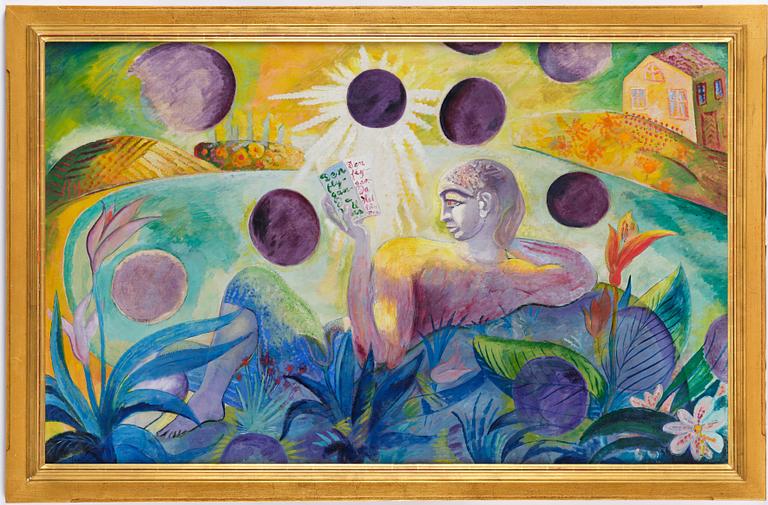

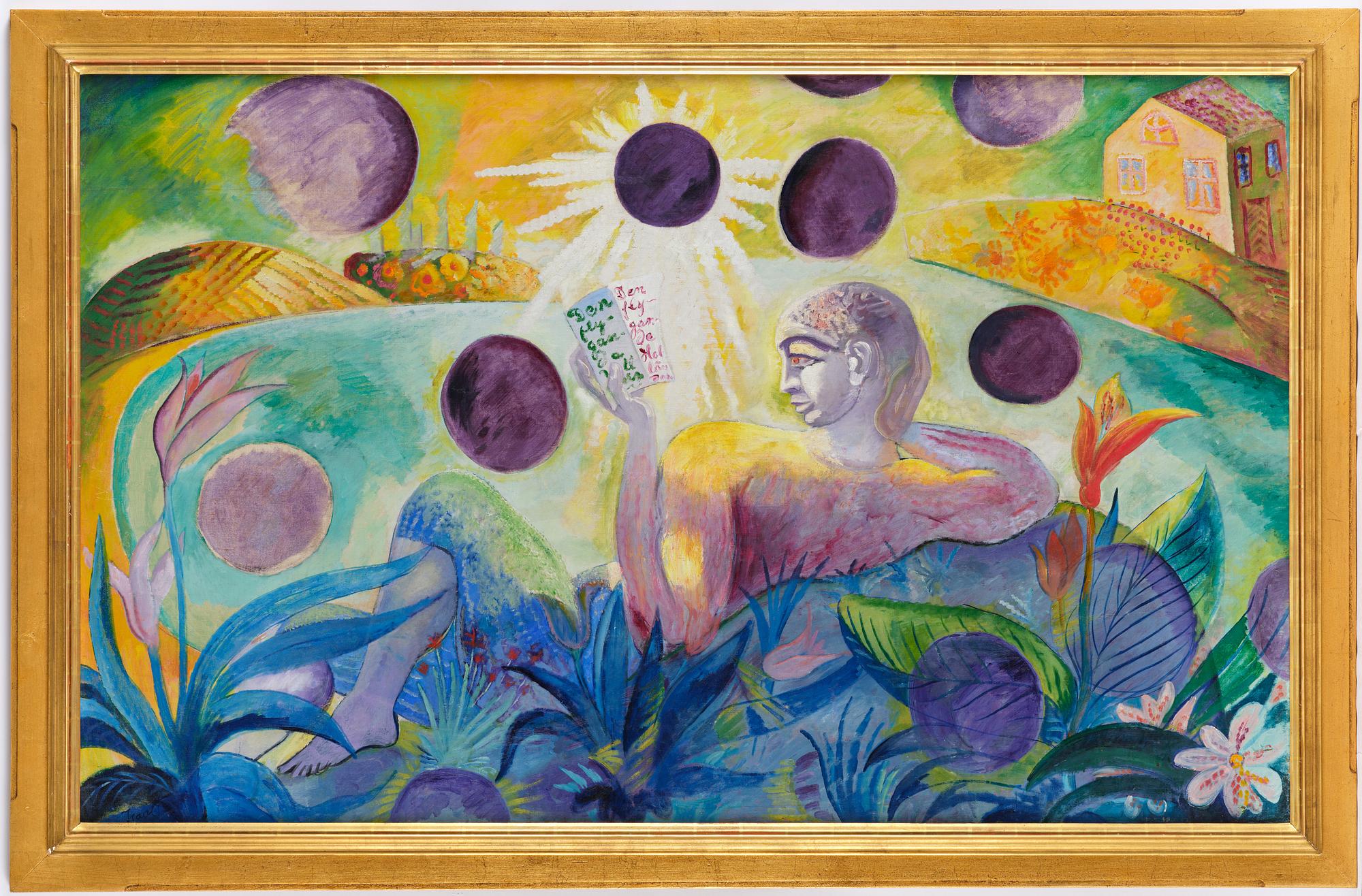

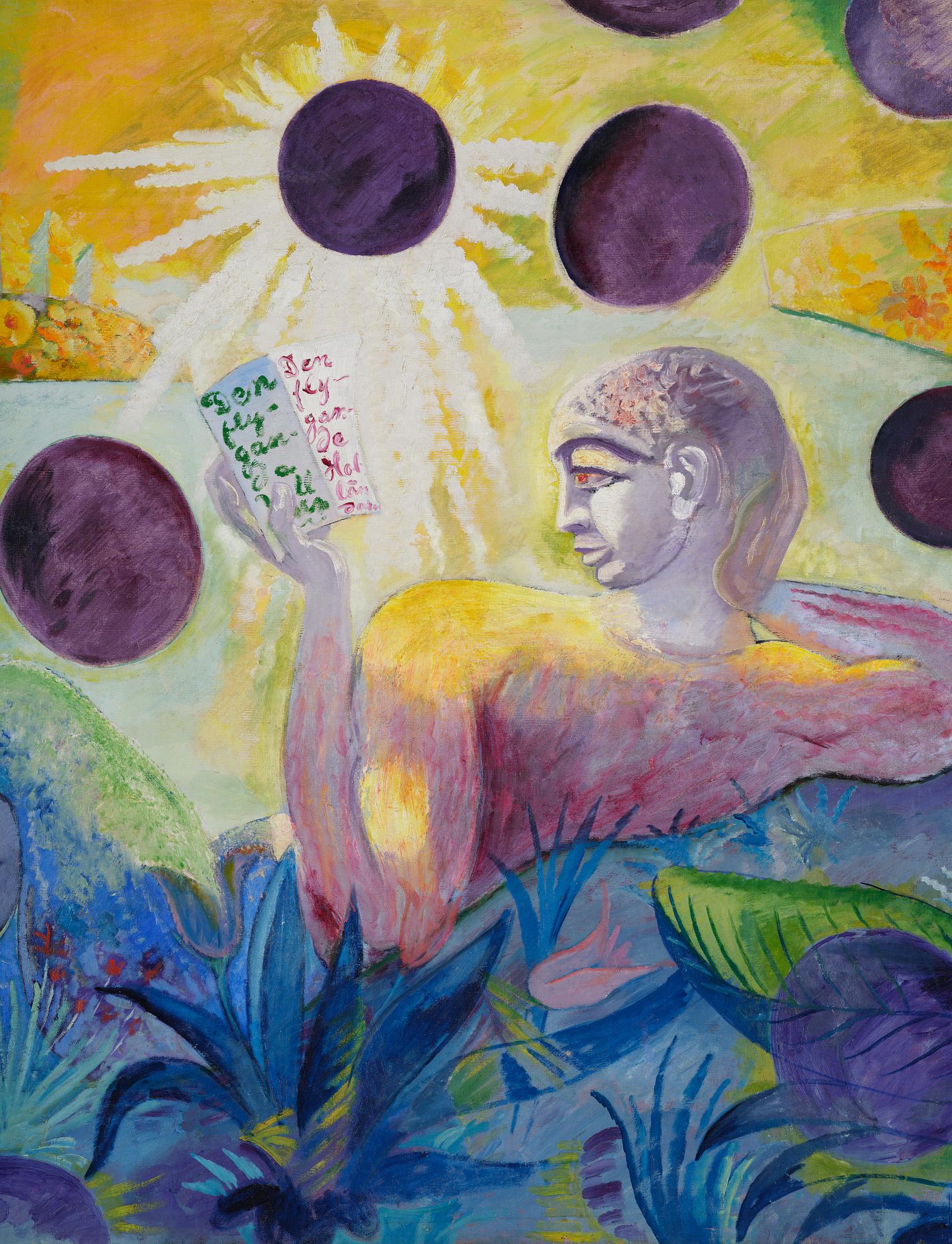

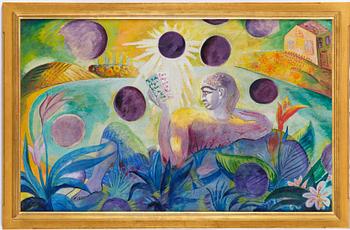

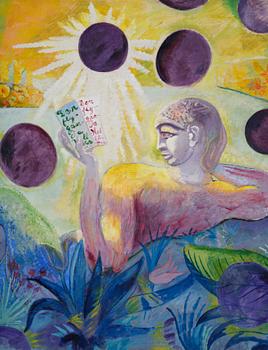

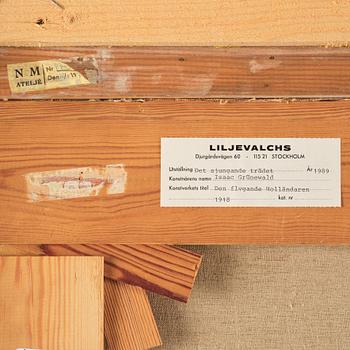

"Den Flygande Holländaren" (Soluppgång)

Signed Isaac. Executed 1916-18. Canvas 125 x 200 cm.

Exhibitions

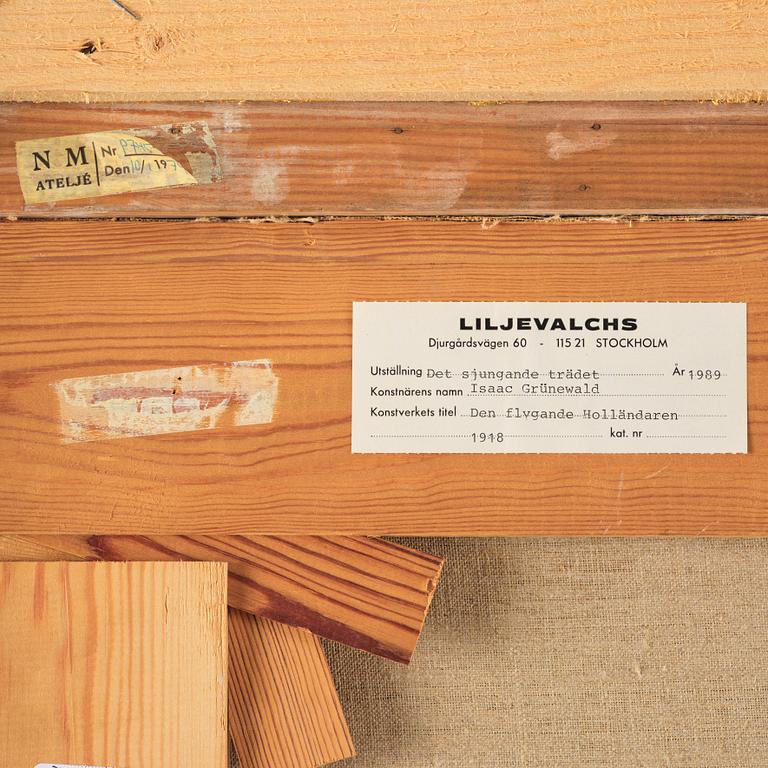

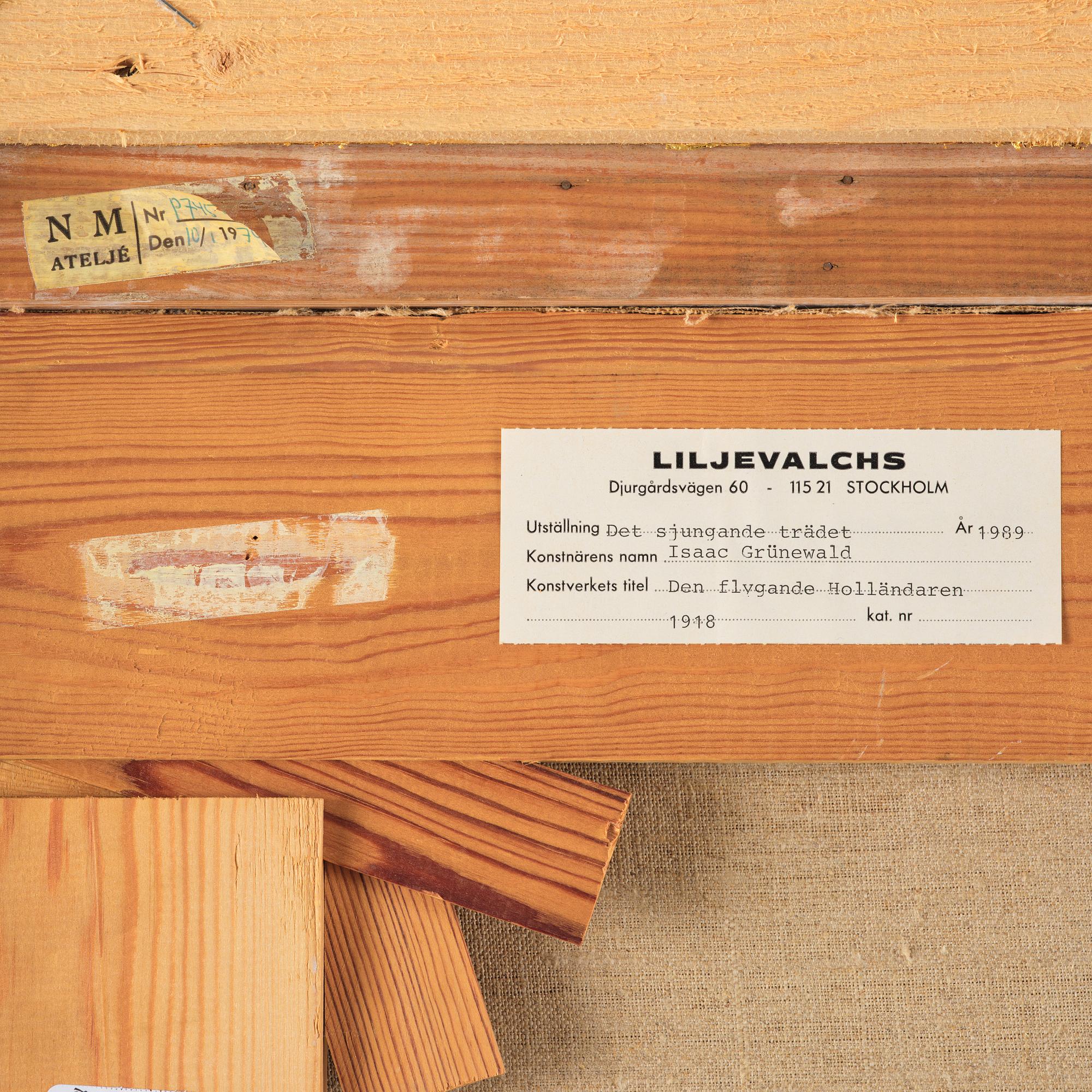

Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm, "Konstnärsförbundet", catalogue No 2, May - June 1916, cat. no 182. (listed under the title "Soluppgång").

Liljevalchs konsthall, Stockholm, "Expressionist Exhibition", catalogue no 12, May 1918, cat. no 85 (listed under the title "Soluppgång").

Liljevalchs Konsthall, Stockholm, "Det sjungande trädet", 8 September - 5 November 1989, cat. no 75.

Bukowski Auktioner, Stockholm, "Orientalen", 15-18 September 2011.

Literature

Bernhard Grünewald, "Orientalen-Bilden av Isaac Grünewald i svensk press 1909-1946", 2011, illustrated in colour p. 95.

More information

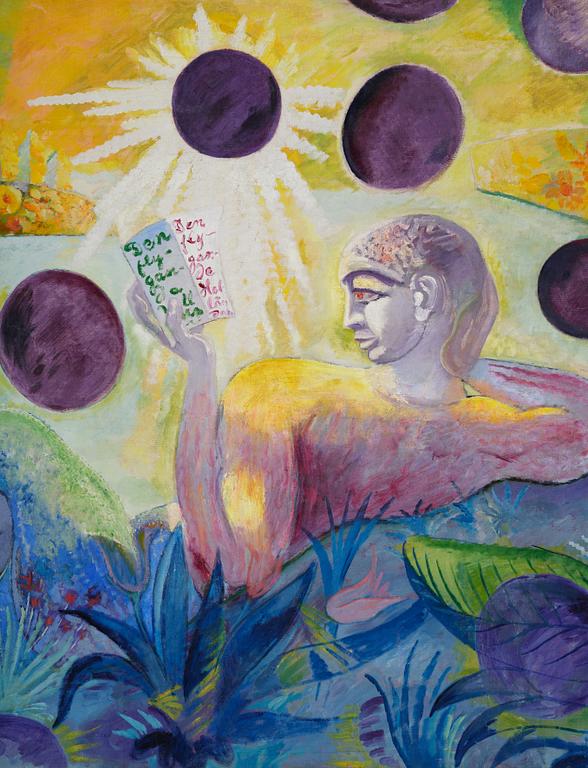

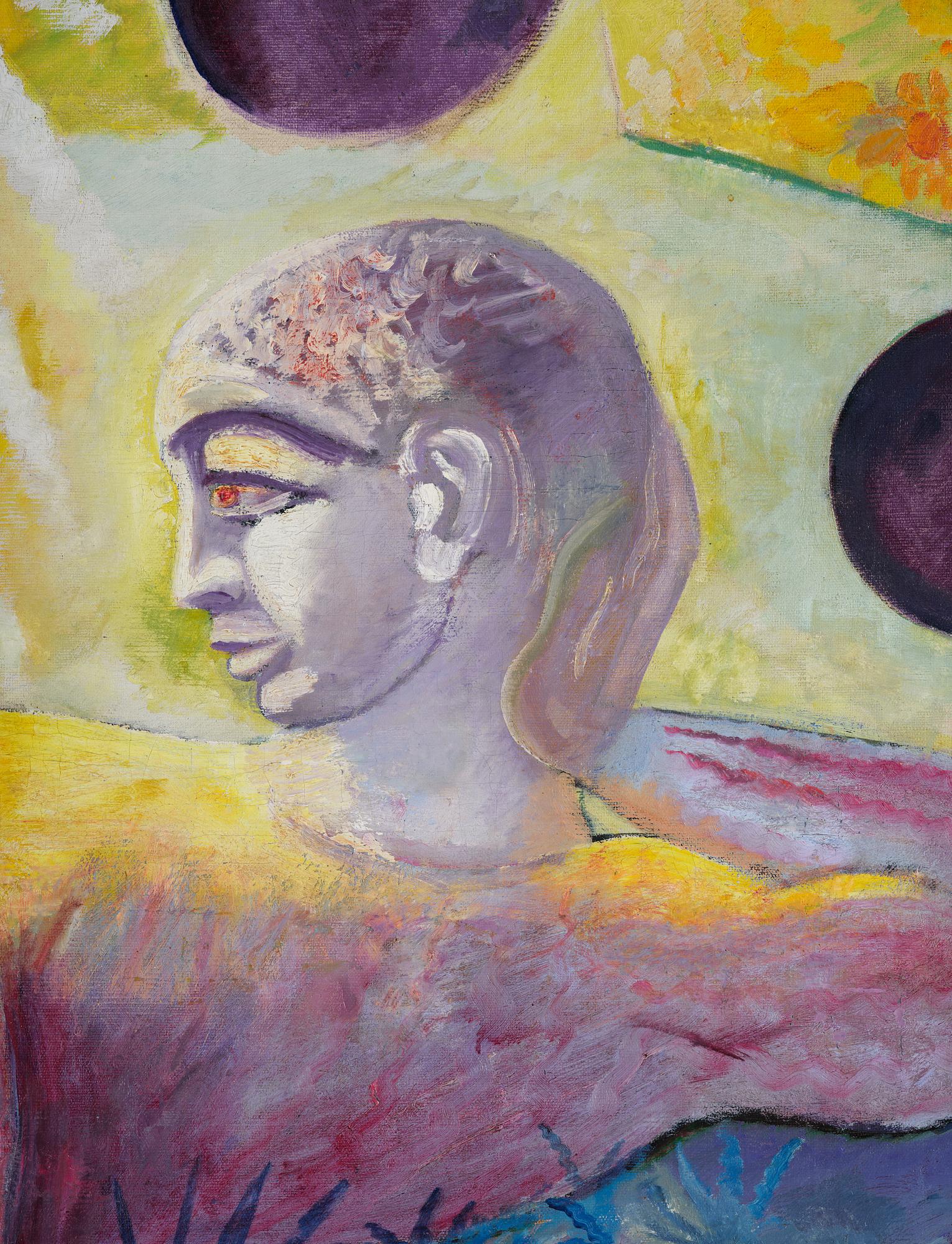

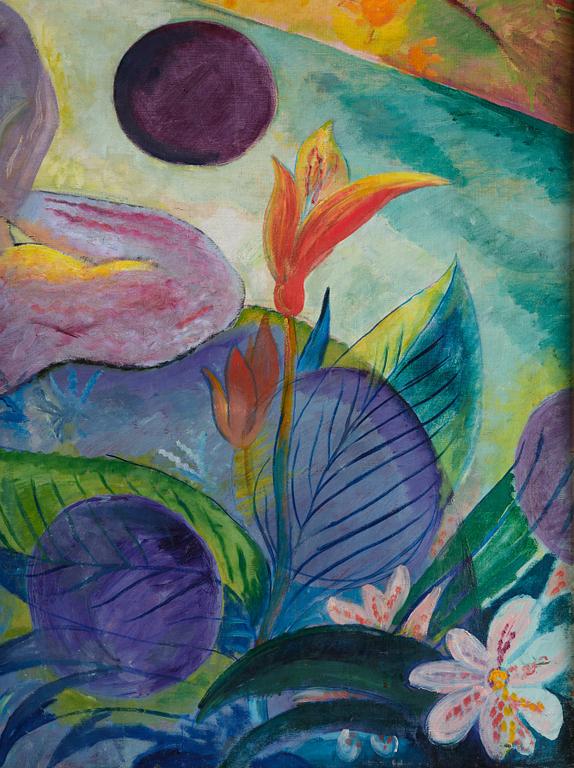

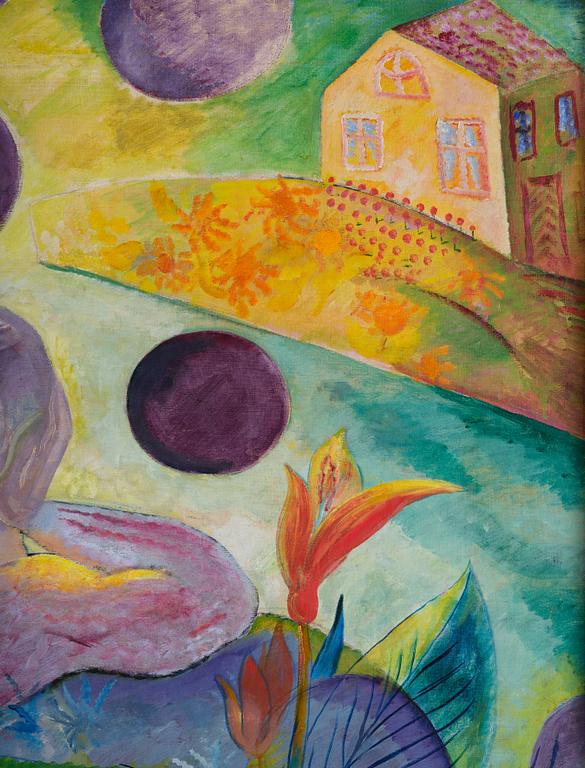

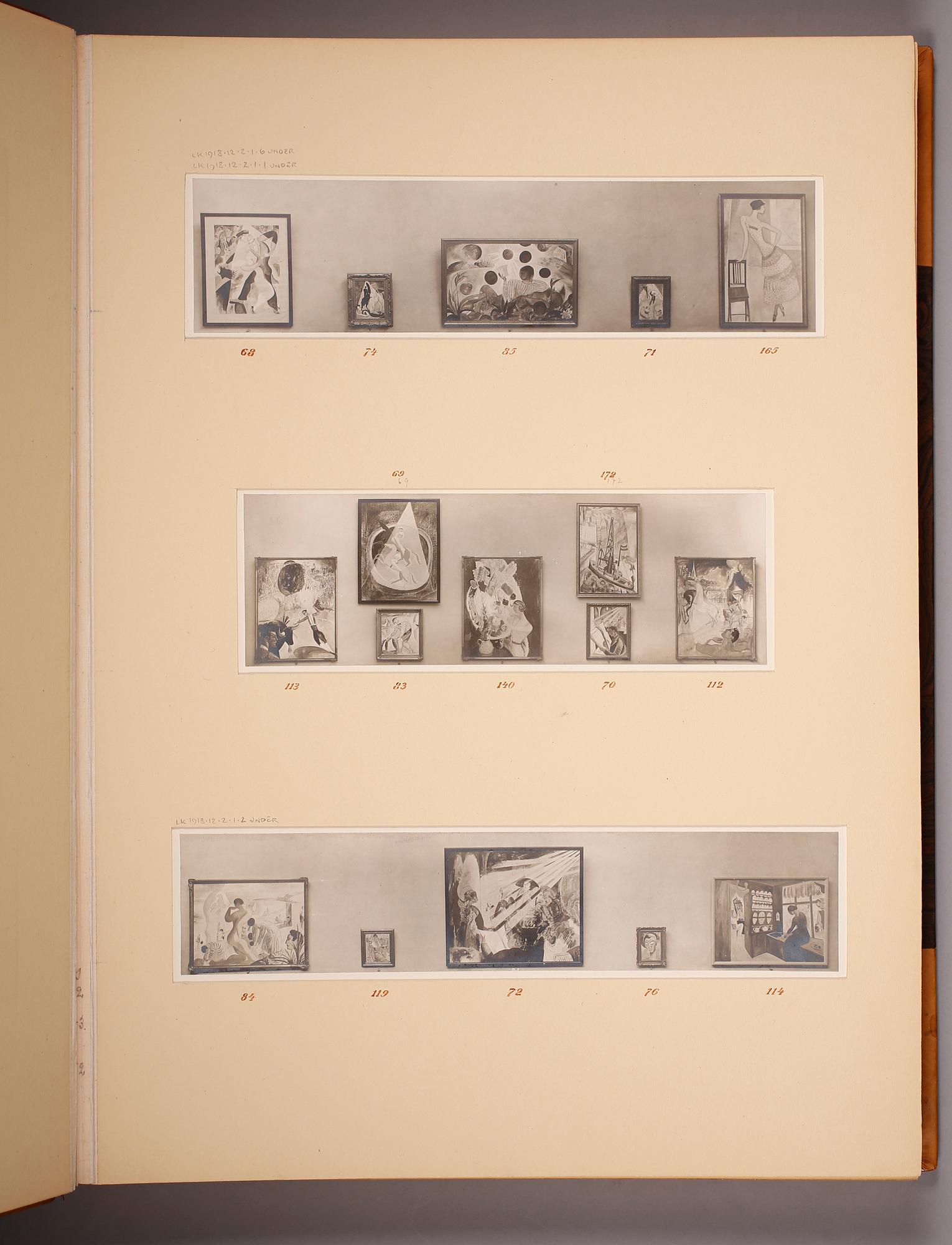

The first time Isaac Grünewald exhibited the monumental painting The Flying Dutchman was at the Artists’ Association exhibition in 1916 at Liljevalchs Art Hall in Stockholm. Two years later, in 1918, it appeared at the now legendary “Expressionist Exhibition,” also at Liljevalchs, in both instances under the title Sunset. Comparing photographs from the two exhibitions, one can see that the painting underwent interesting changes. Over the two years, Isaac reworked the motif: in 1916, a reclining young man reads a book against a somewhat hazy coastal landscape; by 1918, the figure’s elegant suit has been replaced with a striped jacket and knee-length trousers, flowers and leaves have been added to the foreground rocks, and the sun has been rendered differently, with strong rays radiating from a dark sun disk. The young man’s face bears clear features of Isaac himself, perhaps somewhat idealized.

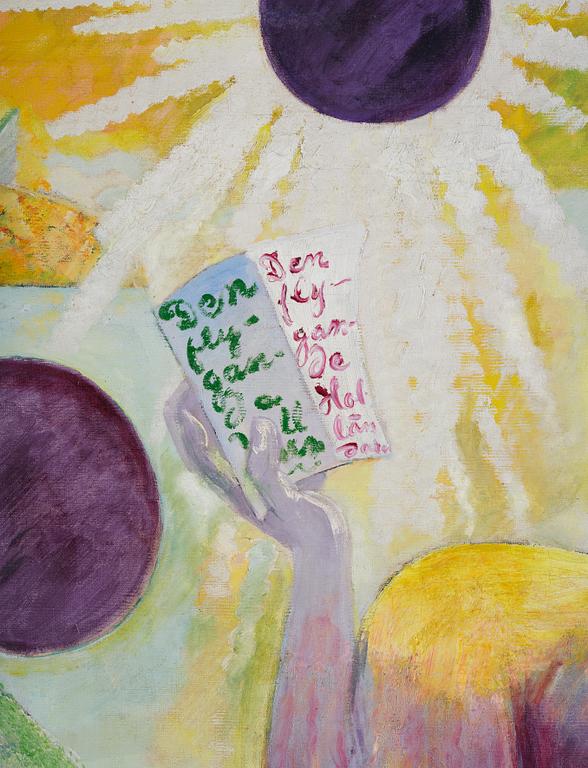

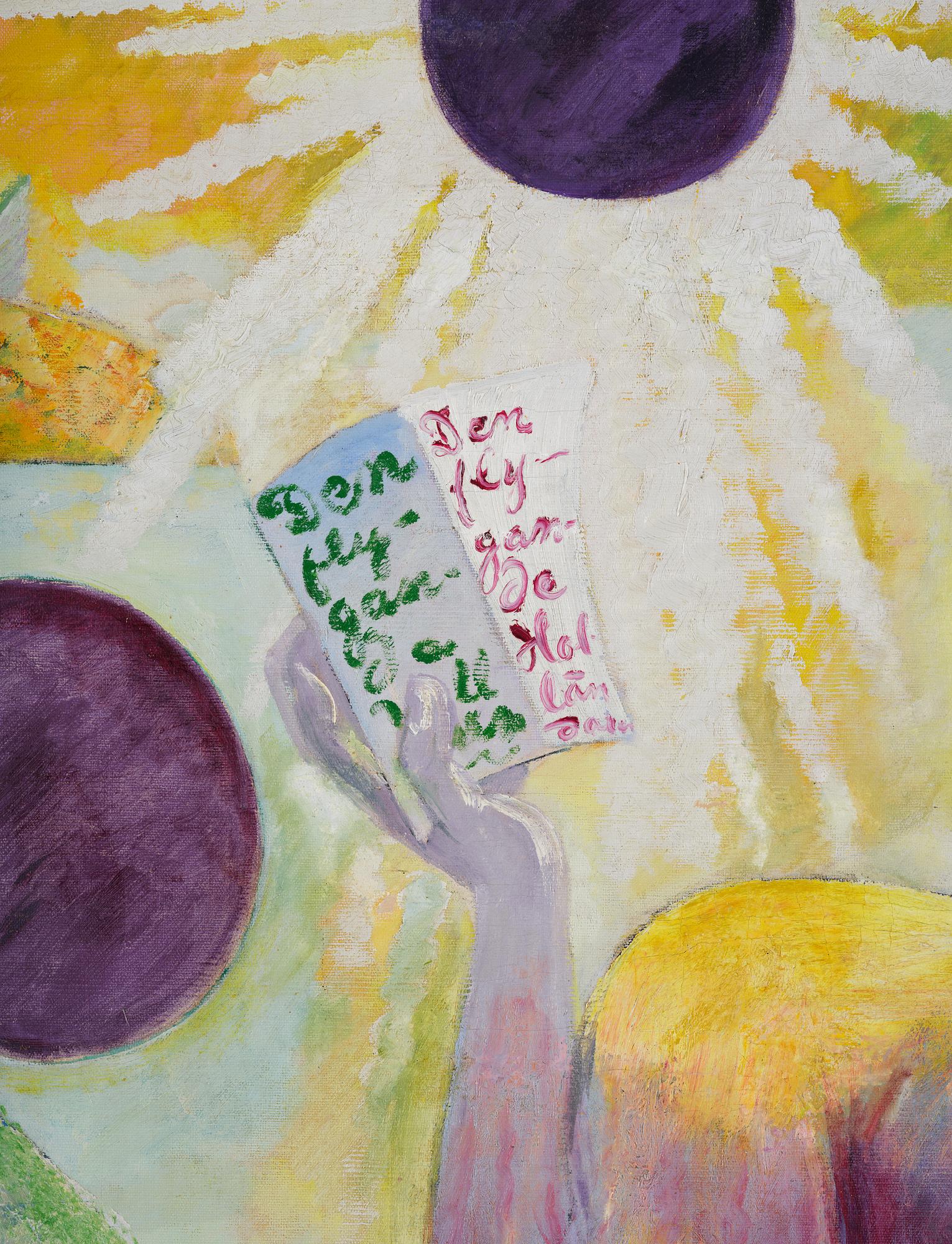

What remains largely unchanged are the round spheres scattered across the surface. Bernhard Grünewald, the artist’s grandson and author of the acclaimed book Orientalen (about Isaac and his portrayal in the Swedish press 1909–1946), notes that the artist himself reportedly stated that the motif originated from a visual idea of so-called “sun dogs,” the atmospheric optical phenomenon appearing as colorful spots in the sky. Well known is the “Sun Dog Painting” in Storkyrkan in Stockholm, which depicts such an event in 1535. The sun dogs appear as colorful spots to the right of the sun.

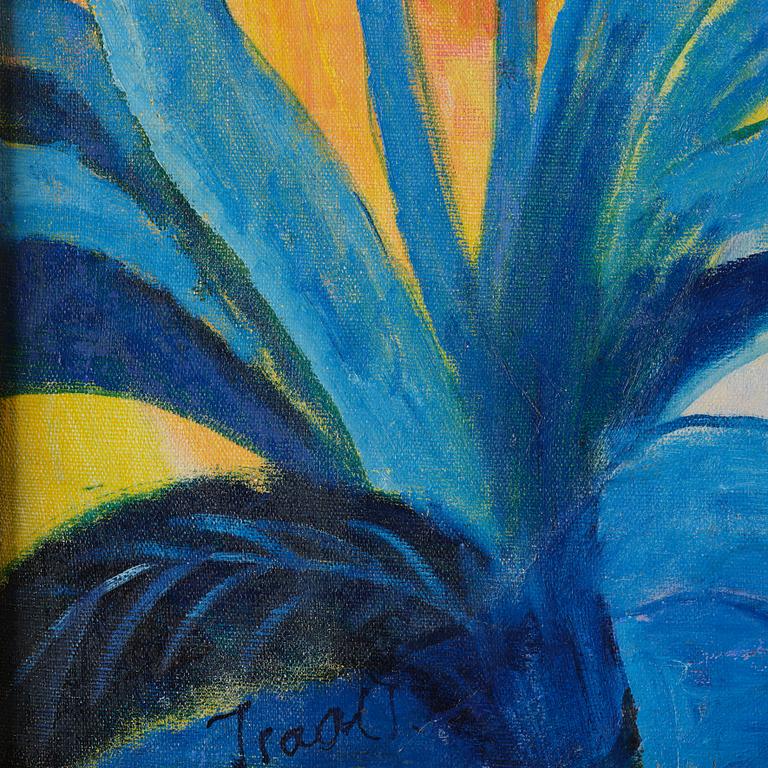

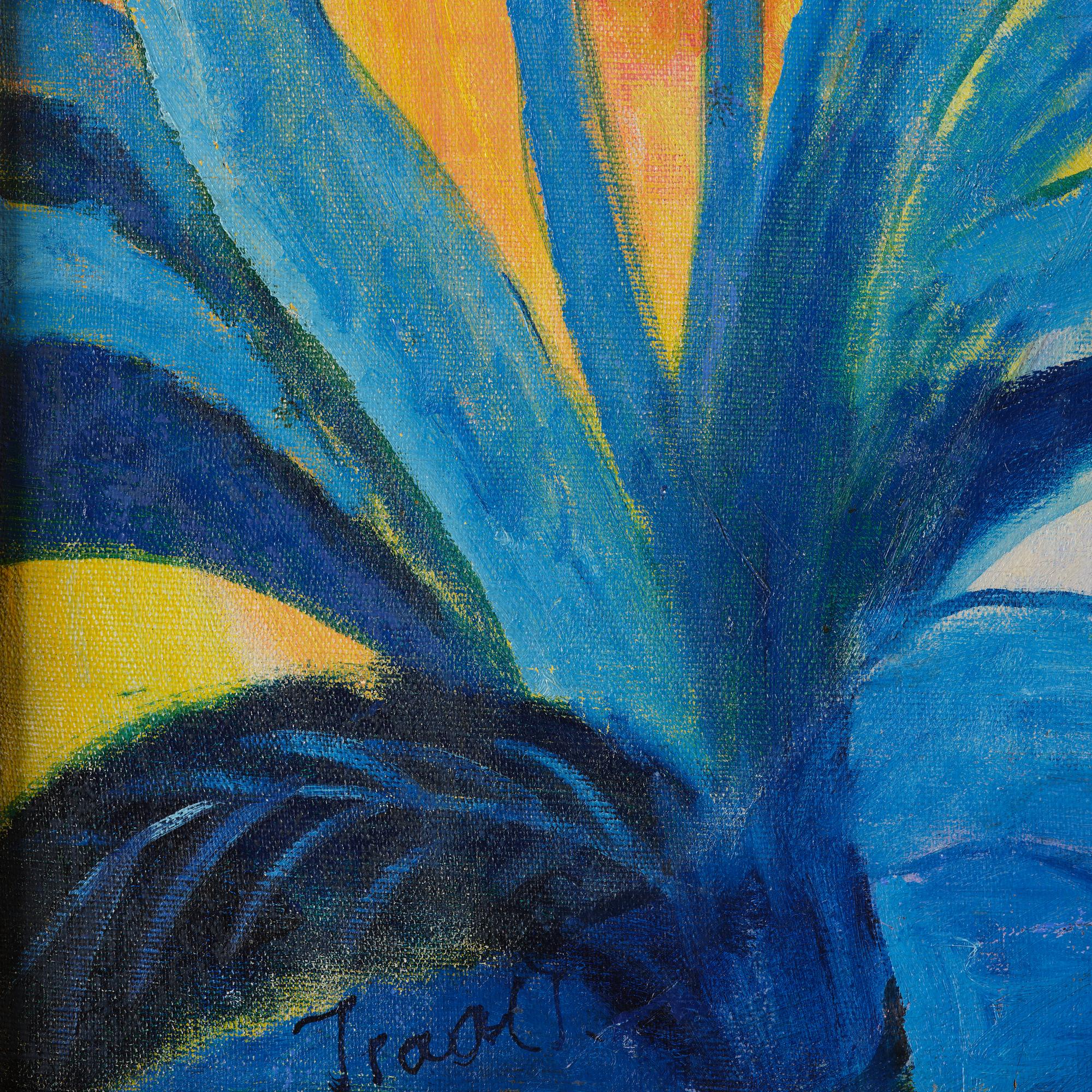

Shortly after the “Expressionist Exhibition,” the artist continued to rework the painting into the version we see today. In 1989, the public had the opportunity to see The Flying Dutchman at Liljevalchs’ renowned solo exhibition The Singing Tree, which also traveled to Norrköping Art Museum and Borås Museum. The painting’s “transformation” is fascinating and strongly linked to Isaac’s situation in the Swedish art scene. The final changes primarily affect the young man’s torso, now naked and more exposed, and the face, which no longer resembles Isaac but looks more like a mask with “Mesopotamian” features. Isaac fundamentally altered the content of the painting—from depicting an elegant stage figure or dandy to portraying the outsider figure he was often identified with in contemporary art debates. A symbolic fantasy, vividly colorful, yet with deeper meaning.

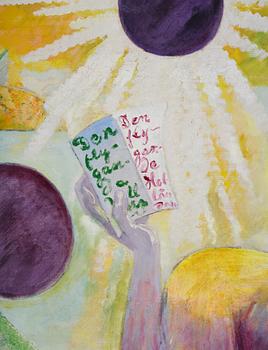

Of particular interest is the book the figure reads with such absorption. The sun’s strong rays illuminate the text The Flying Dutchman, an immensely popular story at the time about a ghost ship and its captain, Vanderdecken (in the Dutch version), who repeatedly fails to round the Cape of Good Hope and finally swears he will succeed regardless of whether God or the Devil opposes him. Naturally, God does not tolerate such blasphemy and immediately condemns the captain and his ship to sail the world’s oceans until Judgment Day. The legend exists in variants across many languages and has inspired numerous writers and artists.

Isaac Grünewald was also, of course, familiar with Wagner’s opera The Flying Dutchman, which premiered in 1872 at the Royal Swedish Opera and was repeatedly performed and celebrated by contemporary audiences. The opera is set on the Norwegian coast and centers on how the curse can be broken if “the Flying Dutchman” finds a woman who can remain faithful to him unto death. Once every seven years, he is allowed to go ashore to search for such a woman. The Dutchman encounters the Norwegian captain Daland, who is impressed by the stranger’s wealth and encourages him to marry his daughter Senta. Senta, who is engaged to Erik, has long been obsessed with the legend of the Flying Dutchman and feels sympathy for him. Deep down, she has dreamed of being the one who could one day free him from his terrible fate. When the two meet, she immediately falls in love. Later, when the Dutchman sees Senta embracing Erik, he becomes irrationally jealous and accuses her of infidelity, then sails away in a rage. Unmoved by Erik’s protests, Senta throws herself into the sea, causing the Dutchman’s ship to sink, and the two lovers ascend to heaven together. The opera’s drama strongly resonates with Isaac Grünewald’s The Flying Dutchman: the beach on the right where the captain lands every seven years, the ship on the horizon, and the blue sea around which the entire story revolves.

In this remarkable artwork, drama, fantasy, and dreams intertwine to create something extraordinary, a work whose counterpart is difficult to find in Grünewald’s oeuvre. Few artworks’ creation and transformation can be traced in such a fascinating way—a process shaped by an artist deeply influenced by contemporary cultural life in art, literature, and music, a scene in which Isaac and his wife Sigrid played a significant role both in Stockholm and in Paris during the 1910s.