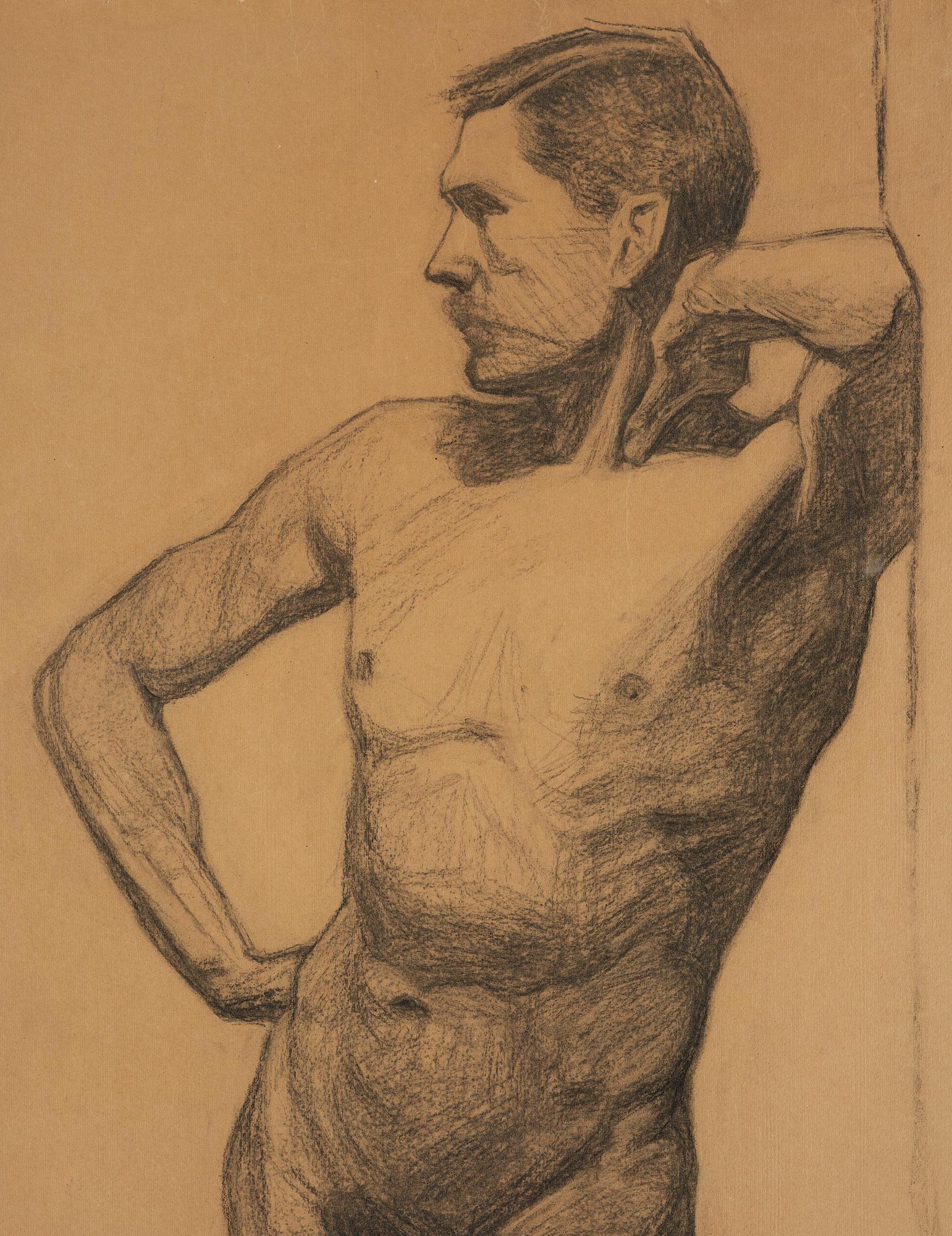

Standing male model leaning against a wooden pillar

Charcoal on paper, 82 x 55 cm.

Tuontiarvonlisävero

Tuontiarvonlisävero (12%) tullaan veloittamaan tämän esineen vasarahinnasta. Lisätietoja saat soittamalla Ruotsin asiakaspalvelumme numeroon +46 8-614 08 00.

Alkuperä - Provenienssi

Provenance within the artist's family.

Julian Hartnoll Gallery, London, 1983.

Seymour Stein Collection, New York

Sotheby’s, London, "19th Century Paintings and Watercolours (Property from the Collection of Seymour Stein)", 26 February 1997, lot 50.

Private Collection, New York.

Private Collection, Great Britain.

Näyttelyt

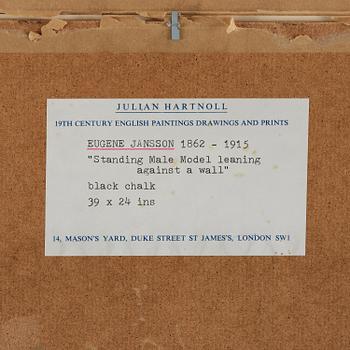

Julian Hartnoll Gallery, London, "Eugène Jansson. The Bath-house period", 26 September - 14 October, 1983, cat. no 12 (with the title "Standing Male Model leaning against a wall").

Kirjallisuus

Julian Hartnoll Gallery, "Eugène Jansson. The Bath-house period", 26 September - 14 October, 1983, London, in the exhibition catalogue titled "Standing Male Model leaning against a wall", cat. no 12.

Muut tiedot

The present work forms part of a group of paintings and drawings originating from the artist’s deceased estate which was handled by Claes Moser, a Swedish art dealer, and exhibited in London by Julian Hartnoll in 1983, where it was acquired by Seymour Stein. Jansson’s estate was inherited by his younger brother Adrian Jansson (1871-1938), who in turn left it in his will to Sebastian Engström (1893 -1975). The drawing is closely related to Eugène Jansson’s famous series of four monumental paintings of naked navy sailors, the subjects of which were taken from the Naval Bathhouse on the island of Skeppsholmen in Stockholm.

The model posing for the present work, is probably the same model that features in the foreground in Jansson’s Bath Painting, from 1908, perhaps Carl Gyllins. This would suggest a date of execution for the present work to c. 1907-08. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Jansson had achieved both critical acclaim and financial success. However, in 1904, he suddenly stopped producing the nocturnal cityscapes that had been so eagerly sought by Swedish collectors. Thereafter, he devoted himself to depicting young workers, sailors, and athletes usually shown nude. In 1901, Jansson travelled to Italy and Germany. In Venice, Jansson attended the opening of the Biennale, where three paintings by him were on display in the Swedish room. Considering his later subject matter, it is particularly interesting to note that Jansson reported to friends that, on this trip, he enjoyed visiting the bathhouses in Munich more than touring museums. During a more extended trip to Italy in 1903, Jansson made many drawings of ancient Greek and Roman statues of nude male figures. These drawings provided an important resource for Jansson in subsequent years. For three years between 1904 and 1907, Jansson systematically sought to remake himself as an artist, mastering the skills needed by a painter of nude male figures. He did not exhibit any of his new works until 1907. The study of ancient classical sculpture during his trip to Italy is thought to have had a major impact on Jansson's change of subject matter. The poses and gestures of some figures in sketches that he executed from life between 1904 and 1907 recall ancient classical statues that he saw during his trip to Italy.

Virtually all of Jansson's drawings that have been preserved demonstrate a convincing rendering of anatomy that is truly remarkable for one who had not undertaken extensive formal studies in the subject. Although the drawings of 1904 to 1907 already indicate his strong preference for younger athletic men, he portrays individuals with varied and distinctive facial features and body types. Despite his use of ancient classical motifs, he succeeds in infusing his life studies with a naturalistic vitality, suggesting movements of muscles even in depictions of seated and standing figures. The soft, subtle handling of light and shade intensifies the sensual appeal of the sketched figures.

The Naval Bathhouse on the island of Skeppsholmen in Stockholm, headquarters of the Swedish navy, was an open-air bathhouse of a wooden structure which used seawater. It was built in 1845 after a design by Fredrik Blom (1781-1853) and closed in 1929. Jansson became a frequent visitor to the Naval Bathhouse in Stockholm by the late 1890s, officially as a cure to heal kidney problems (fig. 9). Photographs of around 1900 show Jansson swimming in the bathhouse pool. It is interesting to note that some of these images capture Jansson mid-air in the same pose that he utilized for the divers in Naval Bathhouse, 1907 (Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm) and Bathhouse Scene, 1908 (Örebro Municipality Art Collection).

During the period that Jansson created his scenes of the Naval Bathhouse, existing Swedish laws against sexual acts between men were being enforced with increased rigour. In 1907, the sculptor Nils Santesson, a close friend of Eugène’s younger brother Adrian, who was also homosexual, was imprisoned for having openly had relationships with men. The baths provided a refuge from oppression because nude sunbathing and swimming were widely regarded as healthy activities. At the bathhouses, men could safely gaze at and associate with other naked men. By the early twentieth century, the bathhouses of Stockholm were widely known to be gathering places for men who desired other men, and they attracted numerous homosexual visitors from all over Europe. Although sexual acts seldom took place at the baths, contacts made there often led to liaisons elsewhere and even to long-term relationships, as in the case of Jansson and Nyman.

Jansson's method in creating the bathhouse paintings differed from that he had employed for his earlier cityscapes. Instead of painting from his imagination, Jansson made numerous preparatory sketches of men at the baths, usually based on photographs (fig. 10); one cannot help but wonder whether Jansson's intense attraction to his new subject matter led to this shift in process. Jansson modified the sketched figures in some significant ways. For instance, model studies relating to the baths, depict men of different ages and of varying degrees of muscular development. In his completed paintings, Jansson populated the baths with the individuals whom he desired: handsome, younger, athletic men. Jansson's late paintings of men eloquently reveal the strong attraction that he felt for his subjects. The artist developed close personal friendships and relationships with several of his models7 - most notably with Knut Nyman (1887-1946), with whom he lived from 1907 to 1913. In looking at Jansson’s drawings, one can understand why he insisted that his subjects were "voluntary models" and friends, rather than studio employees. Most of these men gaze at the artist/viewer with an intensity that is unusual in professional studies. In Seated Young Man (1906, private collection), for example, there is a definite implication of desire in the way that the model, Carl Gyllins, looks up at the artist/viewer – usually Jansson.

In Self-portrait with Bathers, 1910 (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm), Jansson depicted himself at the Naval Bathhouse in the company of beautiful young men. Although he routinely wore no clothes while at the baths, he depicts himself here in an elegant white linen suit, worn with sandals. The broad blue sash around his waist, the yellow tie, and the yellow and blue bands on his straw hat add lively colour accents to his figure. Some scholars have interpreted Jansson's decision to depict himself clothed as an indication of his isolation from others. However, by wearing a costume associated in Sweden with dandies, Jansson provides a clue to his desire for the men around him. Furthermore, the colours of his clothing associate him with the sailors scattered among the crowds around the pool. The sailors wear uniforms of white and blue, highlighted by patches of yellow light, representing reflections of the sun.

Many scholars have described Jansson’s nude male figures as expressions of Open Air Vitalism, a positivistic movement, which was a predominant force in Swedish social and cultural life between 1904 and 1910. Adherents of this movement, which had originated in Germany where it was known as Lebensreformbewegung (Reformation of Life), encouraged nudity as a means to intensify contact with the rejuvenating forces of the sun and natural forces. The movement was a politically diverse social reform movement to prevent individual and long-term societal degeneration as a result of the negative effects of industrialisation and urbanisation. In Sweden, the importance of physical exercise had a long tradition. Pehr Henrik Ling (1776-1839) pioneered the teaching of physical education in Sweden. In 1813 he founded the Royal Central Gymnastic Institute.Towards the end of the nineteenth century several artists in Sweden were at the forefront of the gymnastic movement. The wildlife painter Bruno Liljefors and his two brothers, for example, formed an acrobatic group that performed in public and the painter Gustaf Fjaestad was a Swedish champion in cycling.

Jansson’s paintings of nude men differ in significant ways from those of Johan Axel Gustav Acke (1859-1924) and other artists associated with Open Air Vitalism. For example, rather than showing figures in lush rural settings as Acke did, Jansson represented men in urban settings and interiors. Seeking to express the union of men and nature, Acke and other Swedish artists deliberately blended figures with their environments, utilizing almost identical brushwork for bodies and vegetation. In contrast, Jansson clearly distinguished figures from their settings and emphasized their muscles and other anatomical features, including genitalia (which are depicted in a notably generalized fashion by Acke). Jansson's representations of nude men may best be understood as expressions of his sexuality. In this regard, it is significant that Jansson's decision to focus upon the male figure corresponds with a period in which he seems to have been more open about his attraction to other men than he had been previously. Because of its association with Oscar Wilde and other cosmopolitan homosexuals, the costume of the dandy, adopted by Jansson during these years, can be regarded as a public indication of his sexual preference.

Between 1911 and 1914, Jansson also celebrated the nude male figure in numerous largescale paintings of athletes lifting weights and performing acrobatic exercises in interior spaces. He executed these paintings in the provisional studio that he established at the Naval Bathhouse, which was clearly a dominant presence in his later career. His decision to base an important part of his artistic practice in a premises associated with the emerging homosexual culture provides yet another indication of his willingness to flout repressive conventions. Sailors whom Jansson met at the bathhouse also served as models for many of the studio paintings of athletes, but he also featured his partner Nyman in some of them. In Athletes, 1912 (Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde, Stockholm), Nyman is shown seated on the floor in a pose that recalls the famous ancient Hellenistic statue Dying Gaul (c. 240 BCE, Capitoline Museum, Rome).

In his effort to visualise the exertions of athletes shown in his studio paintings, Jansson occasionally sacrificed the graceful beauty that he achieved in the pool scenes. Furthermore, in order to enhance the impression of athletic exertion, Jansson employed a modified version of the distinctive handling of paint evident in his cityscapes. Among the formal devices that help to convey the strain of muscles are roughly applied, thick strokes of impasto (opaque oil paint) and jagged lines cut into the paint surface with the edge of a palette knife.

During the final three years of his life Jansson also created a group paintings that are distinguished from the previously discussed works by their boldly stylised construction of the figures. Typical examples are Two Wrestlers, 1912 (Private Collection) and Sailors' Ball, 1912 (The Maritime Museum, Stockholm). In these pieces, Jansson pushed his experimental handling of paint techniques further than in any other works. Instead of trying to record the appearance of body parts, he utilized the component elements of his art to create formal equivalents to them. Thus, in Two Wrestlers, thick parallel ridges of paint serve to indicate the strained muscles of their legs. Similarly, long, gently curved strokes in the Sailors' Ball evoke the swaying movements of the dance. As in these examples, most of the pictures in this group show clothed figures in public venues, such as dance halls and circus arenas. Also in contrast to his other figurative paintings, Jansson includes women in these scenes, although in such secondary roles as dance partners and spectators.

Jansson's figurative paintings were greeted with much less enthusiasm than his earlier cityscapes, and they generally received only lukewarm praise from critics. However, three of the foremost collectors in Sweden at the time - Ernest Thiel, Prince Eugen and Klas Fåhreus - all purchased prominent works by him.

The highly publicized Olympic Exhibition organized by the Artists' Union (Konstnärsförbundet) in 1912 in a specially built pavilion in the vicinity of the Stockholm Stadium, featured several of Jansson's paintings of athletes. These were the focus of the most extended analyses of Jansson's figurative work to be published during his lifetime. The critic Tor Hedberg was convinced that Jansson’s achievement marked a milestone in the history of Swedish art:

”By means of this exhibition, the male form, boldly and supremely, has made its entry into Swedish painting, not as a more or less academic study from models, deprived of real life, in an artificial pose, with neither exertion nor repose, surrounded by atmospheric light, using all the contemporary advantages in colour, model arrangement and gesture; they are products of an utterly creative, original art and at least within Swedish art I know nothing to match it.”

The critic Axel Gauffin emphasised that Jansson’s figure painting should not to be conceived from a traditional academic viewpoint, but as portrayals of reality:

”We should not expect of these nudes an academic study with a traditional treatment of skin any more than we should of the impalpable, attractive colour play of our expressionists. What Jansson is seeking is the opposite, he is seeking nerves and muscles under the surface, a living ècorchè.”

Jansson’s pictures of naked bathers and athletes was to a large extent an expression of Open Air Vitalism. Today, however, they are frequently viewed from a homoerotic viewpoint. In 2020-21, for example, the painting The Naval Bathhouse from 1907 was lent by Thielska Galleriet to IVAM - Institut Valencià d’Art Modern - in Spain for the exhibition Moral dis/order. Art and sexuality in Europe between the wars, which focused on sexuality and morality in Europe in the 1920s and 30s.

Lena Rydén

Chef konst, specialist modern konst / Head of Art, Specialist Modern Art

+46 (0)707 783571

Bukowski Auktioner AB, Arsenalsgatan 2

Box 1754, 111 87 Stockholm, Sweden

+46 (0)8 614 08 00 www.bukowskis.com

signatureImage

Bukowskis – Arts & Business I Part of the Bonhams Network

Privacy Statement: This email, along with attachments, is confidential and intended for the use of the intended recipient(s) only. If you have received this email in error, please notify the sender immediately and then delete it. If you are not the intended recipient, please note that disclosing, copying or distributing any content from this email is strictly prohibited.

Please note that all valuations by telephone and email are preliminary and are subject to change once we have examined the actual object. A valuation by email is not a guarantee, nor does it commit Bukowskis to accept the item for sale at auction.

Lisätietoja ja kuntoraportit

Tietoa ostamisesta

Muiden katsomia kohteita