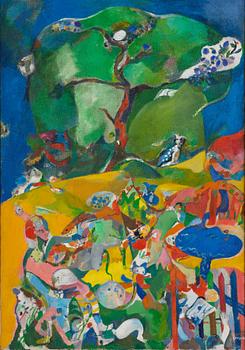

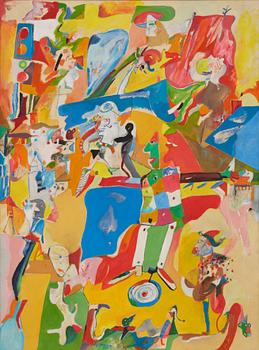

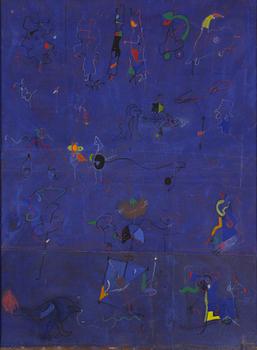

Leif Ericson – A Tribute to Play, Imagination and Music

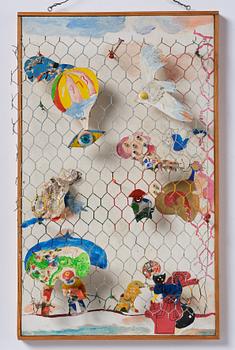

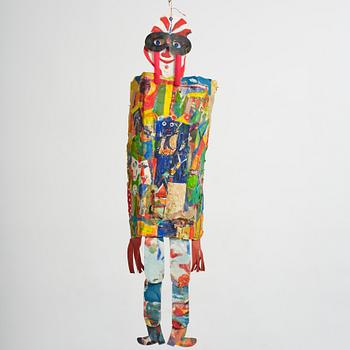

In the autumn of 1958, Leif Ericson exhibited at Liljevalchs alongside 16 other young artists who had studied under Endre Nemes at the Valand Academy of Art. Öyvind Fahlström reviewed the exhibition in Göteborgs-Tidningen and was struck by a new generation of artists who, in a playful and life-affirming way, freely mixed seemingly contradictory visual languages – narrative, abstract, and figurative. Leif Ericson’s artistic practice can be likened to a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art—where the chaos of life and art forms an organic whole. His complex visual world encompasses a wide range of cultural and artistic references. Over the years, he created a unique imaginative universe through thousands of drawings, paintings, mobiles, sculptures, collages, marionettes, and masks. Work titles such as Chaplin in the Zoological Garden, Danish Circus, Jazz Music, and Kino Pollock clearly reveal how his sources of inspiration extend far beyond the conventional horizons of art. In his book Homo Ludens (1938), Johan Huizinga emphasised play as a fundamental and constitutive factor in humanity’s historical and cultural development. The book played a significant role in establishing Homo Ludens as a central concept in 20th-century art, music, and literature. Movements such as Dadaism – with its radical critique of rationality and structure – and Surrealism, with its ideas around automatism, embraced the subversive power of play early on. For artists like Tristan Tzara, Marcel Duchamp, Hans Arp, and Alexander Calder, play was not merely an artistic method but a means of challenging societal conventions and established norms. Calder created his renowned work Cirque Calder between 1926 and 1931 – a miniature circus featuring marionettes made from simple materials like wire, fabric, and found objects. He performed the circus himself, often for friends, artists, and critics, and the freedom of play became an essential part of his artistic expression. Read more

In a similar way to sculptor Alexander Calder, the circus was also, for Leif Ericson, an arena for play and imagination. Like many other 20th-century artists, Ericson also saw early silent film – particularly the slapstick genre with Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin – as a new art form that echoed the circus’s liberating perspective on the world. In addition to being a visual artist, Leif Ericson was also a drummer and jazz musician. During his time at Valand, he was already inspired by the soundscapes of jazz. Both early jazz pioneers like Kid Ory and Bunk Johnson, and more modernist-oriented musicians like Chet Baker, created groundbreaking music rooted in improvisation and rhythmic spontaneity – where the music evolved through playful exploration in the moment rather than through formal structure. The intuitive interaction between jazz performers and their audience mirrors the artistic methods of Surrealism and Dadaism, as both celebrate the playful human being – homo ludens.

In his home and studio in Enskede, south of Stockholm, Leif Ericson created a lifelong body of work – a remarkable environment filled with paintings, sculptures, marionettes, and other artworks occupying every room of the house and the lush greenery of the garden. Throughout his life, he exhibited regularly at galleries, art centres, and museums across Sweden, the Nordic countries, and Europe. He also created a number of public artworks around Sweden, such as the sculpture Spel outside Chalmers University in central Gothenburg and Kråkan at Svärdsjö Health Centre in Dalarna. Leif Ericson’s final exhibition, A Journey into Imagination, was held at the artist-run gallery Candyland on Södermalm at the age of 91. There, he presented new paper puppets, jumping jacks, and collages that radiated vitality and joy – entirely untouched by the passage of time.

Picasso is said to have remarked, “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child”. This quote offers a thought-provoking perspective on how difficult it can be to retain the child’s original openness and curiosity in one’s creative work as an adult. Leif Ericson’s artistic practice embodies the idea of the artist as homo ludens – an artist figure with the power to make us less reserved, and more curious, open, and playful in our approach to ourselves, to one another, and to art.

Text by Henrik Orrje

Stockholm June 11 2025

Viewing: September 1–5, Berzelii Park 1, Stockholm

Open: 11 AM – 5 PM