Modern Art & Design Presents Isaac Grünewald

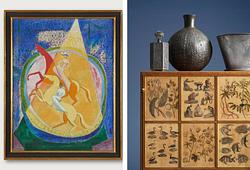

Bukowskis presents the work "Den Flygande Holländaren" (Soluppgång). by Isaac Grünewald at this autumn's live auction, Modern Art & Design – The leading live auction for modern art and design in the Nordics.

The first time Isaac Grünewald exhibited the monumental painting "Den Flygande Holländaren" was at the Artists’ Association exhibition in 1916 at Liljevalchs Art Gallery in Stockholm. Two years later, in 1918, it reappeared at the now-legendary "Expressionistutställningen" (Expressionist Exhibition), also at Liljevalchs—on both occasions under the title Sunset. A comparison of photographs from the two exhibitions reveals that the painting underwent interesting changes. During those two years, Isaac reworked the motif: in 1916, one sees a reclining youth reading a book in a somewhat diffuse coastal landscape; in 1918, the figure’s elegant suit has been replaced with a striped jacket and knee-length trousers, flowers and leaves have appeared among the rocks in the foreground, and the sun has been rendered differently, with strong rays emanating from a dark solar disc. The young man’s face clearly bears Isaac’s own features—perhaps a somewhat idealized likeness.

What remains largely unchanged are the round spheres scattered across the surface. Bernhard Grünewald, the artist’s grandson and author of the acclaimed book ”Orientalen” (about Isaac and his portrayal in the Swedish press, 1909–1946), notes that the artist himself claimed the motif originated from a visual idea of so-called “sun dogs” — optical phenomena in the atmosphere that appear as bright, colorful spots in the sky. Well known is the "Vädersolstavlan" (Sun Dog Painting) in Stockholm’s Storkyrkan Cathedral, which depicts such an event in 1535. Sun dogs appear in the sky as colored spots to the right of the sun.

Shortly after the "Expressionistutställningen" the artist continued to rework the painting into the version we see today. In 1989, the public once again had the opportunity to see "Den flygande holländaren" at Liljevalchs’ much-discussed solo exhibition "Det sjungande trädet", which later traveled to Norrköpings konstmuseum and Borås museum. The painting’s “transformation” is intriguing and deeply connected to Isaac’s position within Swedish artistic life. The final changes involve, above all, the youth’s now naked upper body—more exposed—and the face, which no longer resembles Isaac’s but rather looks like a mask with “Mesopotamian” features. Isaac had, in effect, changed the meaning of the painting: from depicting an elegant performer or dandy to portraying the foreign, outsider figure he was so often labeled as in the contemporary art debate. A symbolic fantasy—vividly and beautifully colored, yet with a deeper significance.

Of great interest is also the book that the figure reads with great intensity. The sun’s strong rays illuminate the text "Den flygande holländaren", an immensely popular story at the time about a ghost ship and its captain, Vanderdecken (in the Dutch version), who repeatedly fails to round the Cape of Good Hope and finally swears he will succeed, whether God or the devil opposes him. Of course, God will not tolerate such blasphemy and condemns the captain and his ship to sail the seas until Judgment Day. The legend exists in many variations across different languages and has inspired numerous writers and artists.

Isaac Grünewald was, of course, also familiar with Wagner’s opera The Flying Dutchman, which premiered in 1872 at the Royal Opera in Stockholm and was repeatedly performed and highly praised at the time. The opera takes place off the Norwegian coast and centers on how the curse can be broken if The Flying Dutchman finds a woman who will be faithful to him until death. Once every seven years, he is allowed to go ashore to search for such a woman. The Dutchman meets the Norwegian captain Daland, who is impressed by the stranger’s wealth and encourages him to marry his daughter Senta. Senta, already betrothed to Erik, has long been obsessed with the legend of the Flying Dutchman and has pitied him deeply. Deep down, she has dreamed of being the one who could one day free him from his dreadful fate. When the two meet, she immediately falls in love. Later, when the Dutchman sees Senta embrace Erik, he becomes violently jealous and accuses her of infidelity, then sails away in a rage. Unmoved by Erik’s protests, Senta throws herself into the sea. As a result, the Dutchman’s ship sinks, and the two lovers ascend to heaven together. The drama’s strong parallels to Isaac Grünewald’s The Flying Dutchman are unmistakable—the shore to the right where the captain lands every seven years, the ship on the horizon, and the blue sea around which the entire story revolves.

In this impressive artwork, drama, fantasy, and dreams intertwine to create something extraordinary—something with few equivalents in Isaac Grünewald’s oeuvre. Rarely can the genesis and transformation of an artwork be followed in such a fascinating way—a process that took place in an artist deeply influenced by the contemporary cultural life of art, literature, and music, the very scene in which Isaac and his wife Sigrid played a vital role, both in Stockholm and in Paris during the 1910s.

To the catalogue

The work will be sold at Modern Art & Design

Estimate 1 800 000 - 2 000 000 SEK

Catalogue online November 4

Viewing November 12–17, Berzelii Park 1, Stockholm

Live auction November 18–19, Arsenalsgatan 2, Stockholm

Read more about Modern Art & Design

All works by Isaac Grünewald at Modern Art & Design

Hammer price

150 000 SEK

Estimate

100 000 - 125 000 SEK

Hammer price

2 350 000 SEK

Estimate

1 800 000 - 2 000 000 SEK

Hammer price

1 550 000 SEK

Estimate

800 000 - 1 000 000 SEK

Requests & condition reports

Stockholm

Louise Wrede

Head of Art Department, Specialist Contemporary Art, Private Sales

+46 (0)739 40 08 19