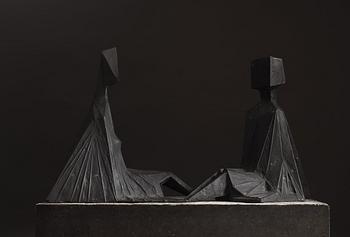

Lynn Chadwick

"Pair of sitting figures"

A pair (2). Signed Chadwick and dated -72. Numbered 3/6 and marked 654 M (Masculine) and 654 F (Feminine). Foundry mark Lypiatt Foundry (England). Bronze, dark patina. Height 57 (22 1/2 in.) and 61.5 cm (24 1/4 in.).

Note: If your online bid exceeds SEK 3 million, you will need a bank reference. Please contact our customer service to be cleared for this level of online bidding.

Provenance

Marabou Collection, Sundbyberg/Upplands-Väsby, Sweden (acquired from Lypiatt Foundry Ltd., England, October 1974).

Kraft Foods Sverige AB, Upplands-Väsby, Sweden.

Literature

Henning Throne-Holst, "Ur Marabous byggnadshistoria", 1977, illustrated in photo, p. 41.

Ragnar von Holten, "Art at Marabou", 1990, illustrated and mentioned p. 10.

Dennis Farr and Éva Chadwick, "Lynn Chadwick : sculptor : with a complete illustrated catalogue, 1947-1988", 1990, compare with No 654.

More information

Copy of receipt from Lypiatt Foundry Ltd enclosed.

“More than human”

Lynn Chadwick’s characteristic figures are immediately distinguishable. They have their very own address, with a distinct style that resembles no other. Majestic strangers, enigmatic, never relaxed – but alert. With their geometrically simplified forms and jaggedly draped capes they awaken associations and fascination. Chadwick repeatedly made sculptures of couples, especially where one figure is female and the other male. From his variations on the sculpture “Teddyboy and Girl” in the 1950s, and throughout his subsequent production, he returned to the couple, in various constellations and postures: seated, reclining, dancing, walking, winged and mantled. The relationship and tension between the two subjects of the couple was a theme he explored throughout his oeuvre.

“It seems to me that art must be the manifestation of some vital force coming from the dark, caught by the imagination and translated by the artist´s ability and skill into painting, poetry, sometimes music. But whatever final shape, the force behind it, as the man said of peace, indivisible. When we philosophise upon the force, we lose sight of it. The intellect alone is still too clumsy to grasp it. The wood is lost in the trees. The intellectual, in his sincere desire to understand by reason, is weary of art which eludes all definitions.” Lynn Chadwick

Lynn Chadwick made his debut on the British art scene just after the Second World War, together with a new generation of artists. Europe lay in ruins, the world was in shock after witnessing the horrors of war, genocide and the effects of the atom bomb. Artists had to relate to this shattered world. Chadwick was an RAF pilot during the war. His desire to devote his life to art had emerged while he was still a young man, but his parents' disapproval forced him to compromise, and he instead trained to be an architect. Before the war, he worked as a draughtsman for an architectural firm. He lacked any formal education in art, and it is perhaps possible to discern the terse geometry of architectural drawings in his oeuvre. When the war ended, Chadwick was full of longing to create, to achieve something new. In his own words: “... some of us felt after the war that we had to make something and that painting was exhausted as far as this attempt to make something was concerned. Actually, we didn’t – at least I didn’t – think of sculpture as such. We thought of construction, of building with our hands.” It took some time, however, before he dared to take the step fully, so he continued working successfully as a designer and interior architect for some years. In the late-1940s, he made his living designing exhibition stands, furniture and wallpaper, alongside his career as an artist.

Chadwick’s first works of art were abstract kinetic constructions which are occasionally compared to Alexander Calder’s mobiles. Chadwick’s mobiles, however, have a distinctively air-borne character, suggesting birds or aeroplanes. These early works are not entirely three-dimensional, but have the nature of flattened structures. He soon gave up making mobiles and went on to create more stable works. These consisted of angular, jagged formations in open compositions of metal and broken glass. In the early 1950s, they began transforming from abstract shapes into more animal-like, or beastly, creatures. These beasts are not intended to represent existing animals; instead, they are vaguely reminiscent of birds, insects and monsters. The former open structures developed into more massive volumes. By the mid-1950s he had mastered his technique fully and achieved his own evocative style. A vast bestiary of monsters, imaginary birds and figures appeared and were to inhabit his artistic universe from then on. The major breakthrough in his career came in 1956, when Chadwick was awarded the prestigious International Prize for Sculpture at the 28th Venice Biennale. His art was acknowledged internationally and he sold numerous works to both public and private collections. Two years later, he moved with his family to Lypiatt Park, a Tudor manor house in Gloucestershire, England. At the Venice Biennale in 1988, he exhibited his magnificent sculpture “Back to Venice”, two monumental seated figures. This return, more than 30 years after his breakthrough, can be seen as a manifestation of a long and successful artistic oeuvre. Lynn Chadwick is now recognised as one of the most important and prominent sculptors of post-war Britain.

The expression in Lynn Chadwick’s sculptures is profoundly linked to his work methods. He was basically an autodidact and invented his own techniques. The sculptures developed as his methods were refined and improved. He describes his own approach as a three-dimensional drawing with metal rods, where he first bent and shaped the rods to the desired form and then welded them together. He then filled the structures that were intended to be solid. Sheet metal was used for some sculptures; applied over the structure, this gave the impression of “metal skin”. Towards the end of the 1950s, he also began casting his sculptures in bronze. Chadwick put great emphasis on patina, and devoted much of his efforts to the surface texture and colour.

“I think that my personal idiom came through my technique, really, and because I worked in this way these images came this way and I couldn’t have done it any other way. I couldn’t have painted this and I couldn’t have carved this in wood because it would have come out quite differently. I wouldn’t have been able to do it. Everything is because of, shall we say, the limitations of my technique.” - Chadwick.

Variations on the triangle are the basic geometric element in Chadwick’s oeuvre, sometimes combined into rectangles. This shape, placed in different orientations, either vertically or diagonally, but rarely horizontally, provides the base for the sculptures and creates the formal tension. Chadwick said that the triangle could be regarded as the simplest sketch of a human or animal figure, and that the whole body could be developed from this shape. He himself stressed that all his works were based on the human figure. “I shall never neglect humanity. Even in my most abstract figure ‘The Pyramids’ I took man as a starting point. The stars can be seen as heads with a single eye and the pyramids can begin to suggest a figure or beast.” –Chadwick.

Although Chadwick is undeniably a modernist sculptor, he did not, unlike most early modernist pioneers, find his formal starting point in ethnic art or classical sculpture. Such references are rarely found in Chadwick’s work. His methods, his use of geometry, his emphasis on construction, have given rise to the idea that his sculptures could be regarded as related to modernist architecture.

The object in this auction, “Pair of Sitting Figures” from 1972, is an exquisite example of Chadwick’s early 1970s output. At this time, he had returned to his human-like figures, after a period in the 1960s of experimenting with more minimalist, abstract works and other techniques, including assemblage and objets trouvées. In order to have total control over the completion of his sculptures, he built his own foundry at Lypiatt Park in 1971, and the piece in the auction is from that foundry. During this period, he began using the schematic geometrical shapes of the triangle and rectangle as symbols for man and woman respectively, and this work plays on the relationship between them. The pair express a distinct spatial presence, with a clear, frontal character. Chadwick never provided any explanations or interpretations for his sculptures. This left viewers free to exercise their imagination and let their associations wander around these mighty, enigmatic beings in their own, strange energy field. The Times’ critic described his sculptures in the following words: “The series of bronze figures imparts that feeling of something more than human, the secret and self-contained power of the idol, which is of the immemorial essence of sculpture.”

Designer

One immediately recognises Lynn Chadwick’s distinctive figures. They have their own visual language, with their formal language resembling no other. These majestic beings appear enigmatic, hardly at rest – rather vigilant. With figures which draw upon simplified geometric forms with sharply draped cloaks, these sculptures evoke associations and fascination.

Chadwick joined a new generation of artists which all debuted on the British art scene shortly after the World War. Europe was in ruin, and the world was arrested in great shock after having experienced the trials and tribulations of war. Chadwick himself was an active participant, having worked as a pilot in R.A.F. Already in his younger years Chadwick was sure that he wanted to direct his career into the world of art, yet his parents disapproved, and thus he was forced to compromise and thus began to study architecture. This is why Chadwick found himself working at an architectural firm before the onset of the war. It can therefore be argued that it is thanks to his architectural training that his sculptures exhibit such a strong geometrical aura. The aftermath of the war left Chadwich longing to create and to achieve something new. Yet it took a while for him to find the courage to fully commit, and thus he continued to have a successful career as a interior designer. In the 1940s Chadwich made a living by designing exhibition stands, furniture, wallpaper simultaneously as he began his career as an artist.

It was thanks to the Venice Biennale of 1952 and 1956 that Chadwick gained international recognition and has since then been thought to be one of the most important artists within the British post-war era. The expression in Lynn Chadwick's sculptures is deeply linked to his methods. For the most part Chadwick is solely self-taught, with his technique having been described as a three-dimensional metal drawing. Chadwick would bend and shape of rods into desired forms, then weld them together, after which he filled in the areas that were to be solid. For various sculptures he utilised metal plates, giving the impression of a “metal skin”. In the 1950s Chadwick began experimenting with bronze. Chadwick placed great emphasis on the patination of his sculptures, meticulously working on surface texture and color nuances.

The triangle is the overarching form in Chadwick’s art, which is sometimes combined with the rectangle. This form, often placed vertically or diagonally (never horizontally), forms the backbone of the sculpture and establishes the formal tension. The artist himself has declared that the triangle is the most stripped-down, basic form of the human body, and it is from this shape people are constructed. He had always clearly expressed how his primary inspiration lay always with the human form.

In contrast to many of his contemporaries who were inspired by ethnographic or classical art, Chadwick found inspiration from modern architecture. The artist never explained the symbolism or meaning behind his sculptures, rather he has left his blank to allow the viewer to form their own interpretations as to the reasonings behind these powerful, enigmatic figures.